Lake Dian in Kunming, the capital of southwest China’s Yunnan province, suffered greatly when, in the 1950s, Chairman Mao Zedong called on the Chinese people to “conquer nature” and reclaim land by filling lakes with soil.

Nowadays, Dianchi, as it’s known in Chinese, effectively acts as Kunming’s main sewage dump—its pollution is a persistent and at times stinky problem for nearby residents and visitors. After the lake’s water quality hit its worst low in the 1990s, the local government took notice and reportedly spent billions of dollars to clean it up. So far, the improvements are hard to spot, according to a mid-December WeChat post from the Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE).

Data collected in the China Environmental Statistical Yearbook show that in 2013 Lake Dian took in 400 million tons of municipal sewage and 8 million tons of industrial waste water, only 1.5 million tons of which was treated before it was dumped. (A lot more waste water from mom-and-pop shops probably wasn’t reported in the official data, the IPE said.) With little to show for all the water cleanup investment, several NGOs, including the IPE—which made the handy, air-pollution-tracking Blue Sky Map app—called for more public information disclosure.

As a growing number of Chinese move to the city, leaving the countryside behind, concerns mount among agriculture experts about the efficiency and affordability of Chinese farming. At McKinsey’s Urban China Initiative 2015 Annual Forum in November, Chinese Agriculture University President Chen Zhangliang said he has been shocked to see Chinese foodstuffs’ dramatic loss of market share to imports over the past 10 years.

In December, U.S.-grown #2 yellow corn was sold in China for U.S.$170.2/ton FOB (or about 1,087 RMB/ton). Even after factoring in import tariffs, the total unit price for the American grain would be 1,560 RMB/ton, still cheaper than Chinese varieties. Australian-produced white sugar sold in China for 4,000 RMB/ton at the port, while the same product from farmers in Guangxi, where Chen worked as an agriculture official, would need to fetch 5,100 RMB to break even. Chen was particularly concerned that government policy sets up a minimum price to purchase grain from farmers in China. With growing imports from overseas, China is hoarding more than enough food for its own citizens to consume. Yet local governments still might need to expand state warehouses to store more purchases from domestic farmers. In 2014, China produced 600 million tons of grain, and imported 100 million tons. These days, it’s not unusual for Chinese to eat pork, beef, and lamb imported from countries thousands of miles away. Consolidation of small and family-size farms and the adoption of machinery, Chen said, is an option to boost Chinese agriculture’s competitiveness. Yet how to address the concerns of farmers put out of work is another policy dilemma.

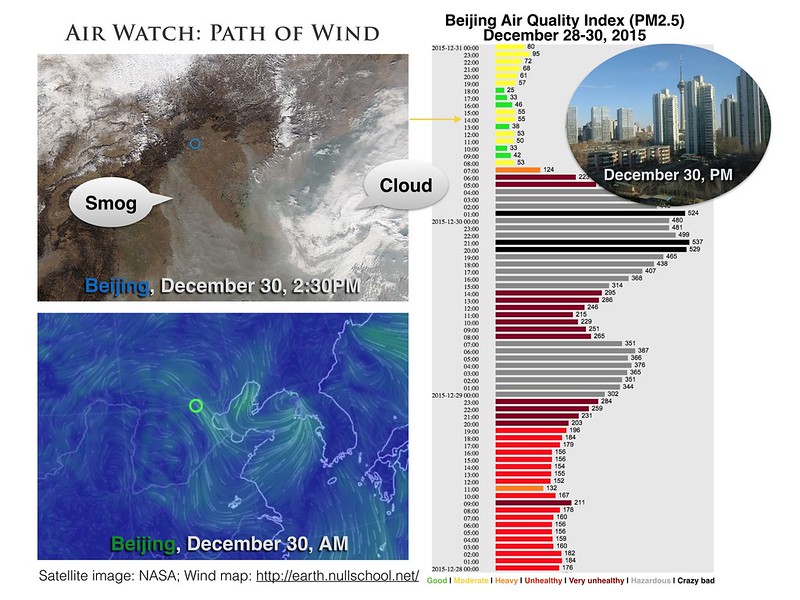

The top image above comes from the NASA Earth Observing System Data and Information System. In the image below, from the wind-mapping website Earth, wind swirls in and around Beijing (the green circle). On the right, the PM2.5 rating scale from Good to Hazardous is from the Environmental Protection Agency’s Air Quality Index (AQI). “Crazy bad” is popular slang for readings above the AQI index; AQI readings were collected from the U.S. Embassy by a Beijing-based programmer with whom I have been in touch for a few years.

Right before New Year’s Eve, Beijing and cities nearby were plagued by another spell of heavy pollution until the wind blew in and cleared the air. The NASA image and the Earth wind-mapping site compare two perspectives from space: one of the smog coverage after the wind blows through, and the other of the winds themselves around Beijing. Of course, when the wind blows in Beijing the capital gets a much-needed breather—in the chart above, see the oval picture of a view of western Beijing, taken from the ground on December 30.

For those living in Beijing this winter, the need for an air purifier has never been greater. It doesn’t take long for the filters in these household appliances to collect enough dust and soot to look gross. This is no surprise. Greenpeace China previously conducted an experiment in which a breathing simulator was strapped to people’s chests to record the dust collected by a small filter over 20 hours. The results are sadly illuminating. Watch our short video, “China’s Air Pollution: The Tipping Point,” to learn more about the experiment:

Environment

01.23.15

China’s Air Pollution: The Tipping Point

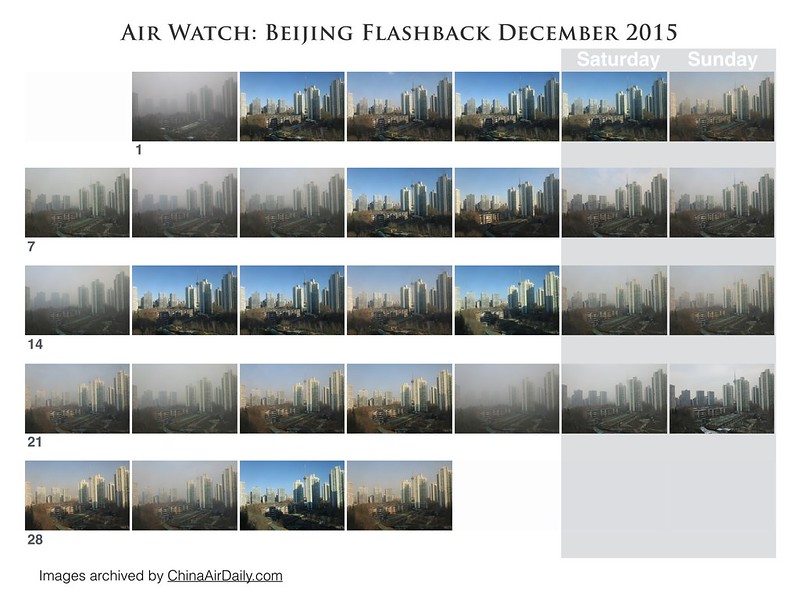

I end this post with a look back at photos of Beijing’s air quality for the full month of December 2015, and conclude, simply, that January’s strong winds could have helped in December...