Among the sixty areas covered in the Communist Party’s “decision” document released after the third plenum of the Eighteenth Central Committee, the most popular among ordinary people is a revision to the family planning policy to allow some couples to have a second child.

This new policy would allow couples that have one parent who grew up as an only child have a second baby. Whether or not a couple should have a second child is a decision that should be made within the family, but in China the right to make that decision has long been in the hands of the government.

The country’s birth rate is already below 1.04, and many academics say the party has acted too late. The aging population and labor shortages are already burdens on the economy, and the willingness of younger generations to have children has hit a historic low. Many academics think that the government should not only allow second children, but that they should do away with family planning policies altogether and in fact begin encouraging families to have more children.

A Small Step

Liu Li, a housewife in Beijing, says that the change eliminates a great deal of hassle for her family. “We had planned to go abroad to give birth to our second baby, but then we calculated that would cost at least 300,000 yuan," she said.

Liu said that many of her neighbors have had a second child by going abroad. This has become something of a trend in recent years. The children are generally brought back to China to be raised.

“Only a very small number go abroad to give birth in order to get a green card,” said Liu, referring to documents that would allow them to reside in a foreign country. “The vast majority go abroad for legal status.”

Liu said bringing a child who has foreign citizenship back to China involves its own headaches.

“The child will eventually want to go to school,” she said. “Education has become a major issue. You can send them to private schools, but that will require yet another big sum of money. To send them to public schools, you have to go through all kinds of procedures, and sometimes even then it's not even possible.”

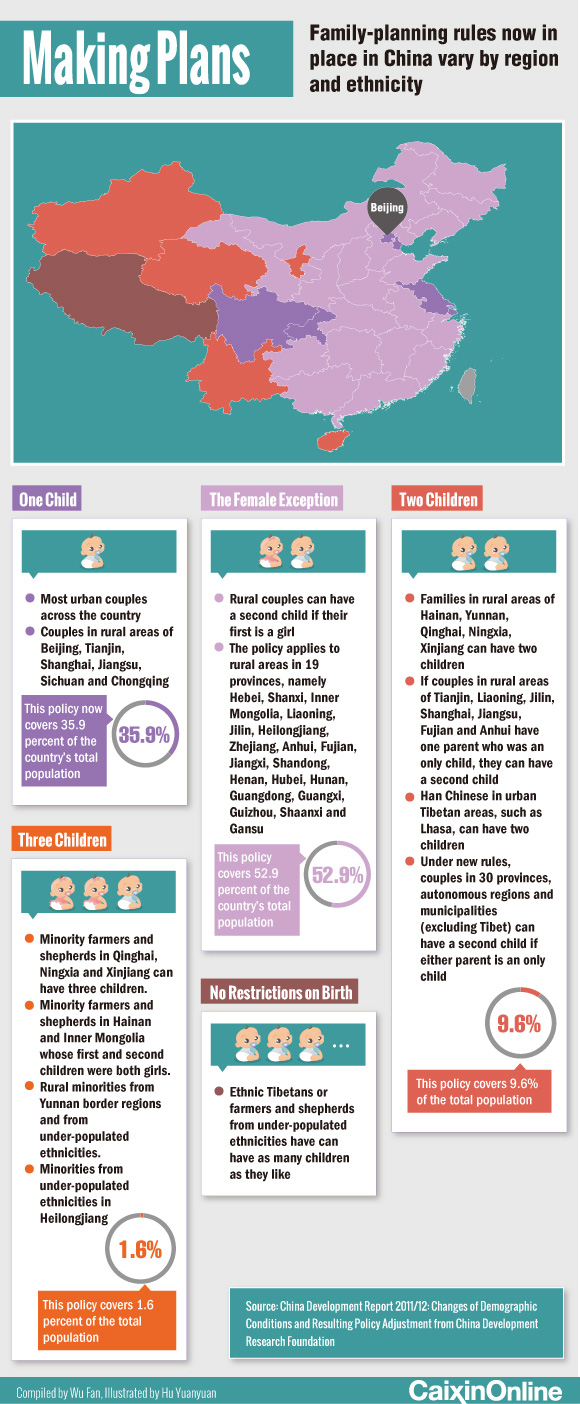

The changes to the so-called One-Child Policy will primarily affect urban families, says Zuo Xuejin, Vice Director for daily operations at the Shanghai branch of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS). “There aren’t many only children in rural villages, so the effects of the policy will be very limited. It’ll affect cities more than anywhere else because only children are concentrated in cities.”

The results of a preliminary investigation into families’ willingness to have more children launched by the National Health and Family Planning Commission—which serves the dual dole of health ministry and family planner—shows that about 15 to 20 million people qualify for the policy revision, and of those about fifty to sixty percent of couples are willing to have a second baby.

Research by the commission indicates that not many couples meet the new criteria. Also, local governments will need time to get measures in place. So in the short term, there should not be any sudden population increase.

Zuo also said the policy change is just a small step. “It won’t have a great impact,” he said.

No Time to Lose

Even though it’s just a small step, the policy change is seen as necessary and important.

“A massive population remains China’s basic national condition, but structural problems of the population are daily becoming increasingly important factors affecting the development of the economy and society,” said Wang Peian, the health commission’s Vice Director.

The country’s birth rates are already low and steadily declining. In the 1990s, the birth rate dropped below the replacement rate. At present it is on par with developed nations. If current policies continue unchanged, the population will rapidly diminish once it hits its peak level, which will affect long-term population growth.

At the same time, problems related to the structure of the population are becoming increasingly vexing. The commission calculated there were 3.45 million fewer people of working age in 2012 than in 2011, and after 2023 the total will drop by an average of 8 million annually.

On the other side of the coin is the rapid aging population. The number of people aged sixty and above hit 200 million this year. That number is estimated to be 400 million by the mid 2030s, when the proportion of seniors to the total population will rise from the current level of one-seventh to one-fourth. The gender ratio will also remain a problem in the long term. As of 2012, it was 117.7 boys to every 100 girls.

There is also the problem of continued shrinking of family sizes. Data from the country’s sixth census in 2011 showed that the average family size in China was 3.1 people, a drop of 0.34 from the 2008 census. More than 150 million families were raising only one child, and the percentage of seniors living alone is rising. The traditional functions of the Chinese family are growing weaker every year.

Abnormalities

Many people have been calling for changes to the thirty-year-old family planning policy, some since the beginning. In September 1980, the party's Central Committee issued an open letter to all party members and members of the youth league that said in part: “In thirty years, the currently very tense problem of population growth can be mitigated, at which point we can adopt different population policies.”

In order to enact controls on birth, the government established family planning administration and service centers on an enormous scale around the country. They empowered officers of the family planning system with two means of enforcement. The first was technological measures, namely birth control services. The second involved “social support fines” levied on families exceeding the number of allowable births.

Slogans such as “IUD after child one, tie your tubes after child two; pregnant after you’ve had your share, abortion’s the trick for you” were commonplace in rural villages in the 1980s. In fact, in some places they are still used. Statistics issued by the former National Family Planning Commission in 2006 showed that the birth-control rate of married women of child-bearing age was 84.6 percent, and the rate of intrauterine device (IUDs) use, female sterilization, and male sterilization was 87.2 percent. Of those, nearly one-fifth had their method of birth control decided for them by family planning officers.

A professor of obstetrics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Fu-xian Yi, estimates that from 1980 to 2009 275 million abortions were performed in the country. He further calculated that 544 million children were born over that period, meaning that “for every three children conceived in China, one ended up aborted.”

Forced birth control was the aspect of the old policy most resented by rural residents. With public opinion pressure building both at home and abroad, the government eventually opted for a more lawful enforcement of the policy while at the same time giving preference to economic measures. Parents who had children outside of state planning paid fines of as much as ten times a city’s annual per capita income. Only after the fines were paid were children given a legal identity.

If the family did not pay the fines on time, family planning departments could apply to the courts for “forced enforcement.” In practice, this often involved violence, such as detaining a pregnant woman or her family members, destroying property, or even forcing the woman to have an abortion.

Using such severe measures, China was able to achieve its population goals. Official calculations show that family planning policies resulted in the “non-birth” of 400 million people. This “to a great extent mitigated the pressure on resources and the environment from excessively fast population growth,” the government said.

But this resulted in some abnormalities. Official statistics show that in 2011 the average number of children born per woman was 1.04. This is much lower than the replacement rate of 2.1.

“Birth Accumulation”

Fears of “birth accumulation” have been cited by critics who wanted to see the policy stay in place. This was a reference to fears of a massive short-term rebound in birth rates if changes were made.

“If everybody tries to have children all in the same year out of competition to be first, there will be a sudden boost to birth rates,” said Lu Mai, Secretary-General of the China Development Research Foundation. “If that’s the case, those children will encounter problems at every stage of their life, whether it be in seeking medical care, attending school, or in the provision of public facilities.”

The foundation issued a report in October 2012 in which it calculated that if families were allowed second children simultaneously in every region of the country, the overall birth rate would soar. In the first few years after the policy was relaxed, the overall birth rate might exceed 4.4. That means the birth of 46 to 48 million babies.

However, research by Wang Guangzhou, a researcher for the CASS Population and Labor Economic Research Institute, found that allowing second children in 2013 would only lead to a small spike in birth rates in 2014, but that the overall birth rate would rise to only about 1.93. That would lead to a maximum of 27 million new babies and a minimum of 15 million.

“Birth accumulation” was simply impossible in the short term, Wang said. Furthermore, it would be impossible for women of child-bearing age who have just had their first child to immediately have a second many reasons, such as high costs.

Data from the Shanghai government shows that 12,000 couples applied to have second children in 2011, but less than half of the women ended up pregnant. The rate of bearing second children among registered Shanghai citizens from January to September 2012 was about eight percent. Thus, beginning in 2004, the city’s government ended a rule that mandated births be separated by four years, and began encouraging some couples to have their second child.

Many academics said that the 2005-2010 period was the most opportune for making adjustments to population control policies, but that the country still had a window for reform. However, a veteran researcher of population policies, professor Li Jianmin of Nankai University’s Population and Development Institute, says this window of opportunity will soon close. “Once the window passes, making reforms will become more difficult.”

Policymakers have already taken the first small step. Now many academics and member of the public hope they will quickly take the second: abolishment of all birth restrictions and even encouragement of births.